In-memory software design in 2025 - from 40GB/s to 55GB/s

In the last blog, we looked at techniques for improving when we were doing partial sums and to reduce the scanned trades we used in-memory indexes using sets.

But what if we simply want to go faster for the complete aggregation?

Up to now, we've been programming for the programmer making the program easy to write and understand, but what if we make the program easy to run for the cpu?

How do we do that? By improving memory locality and structures.

Memory locality

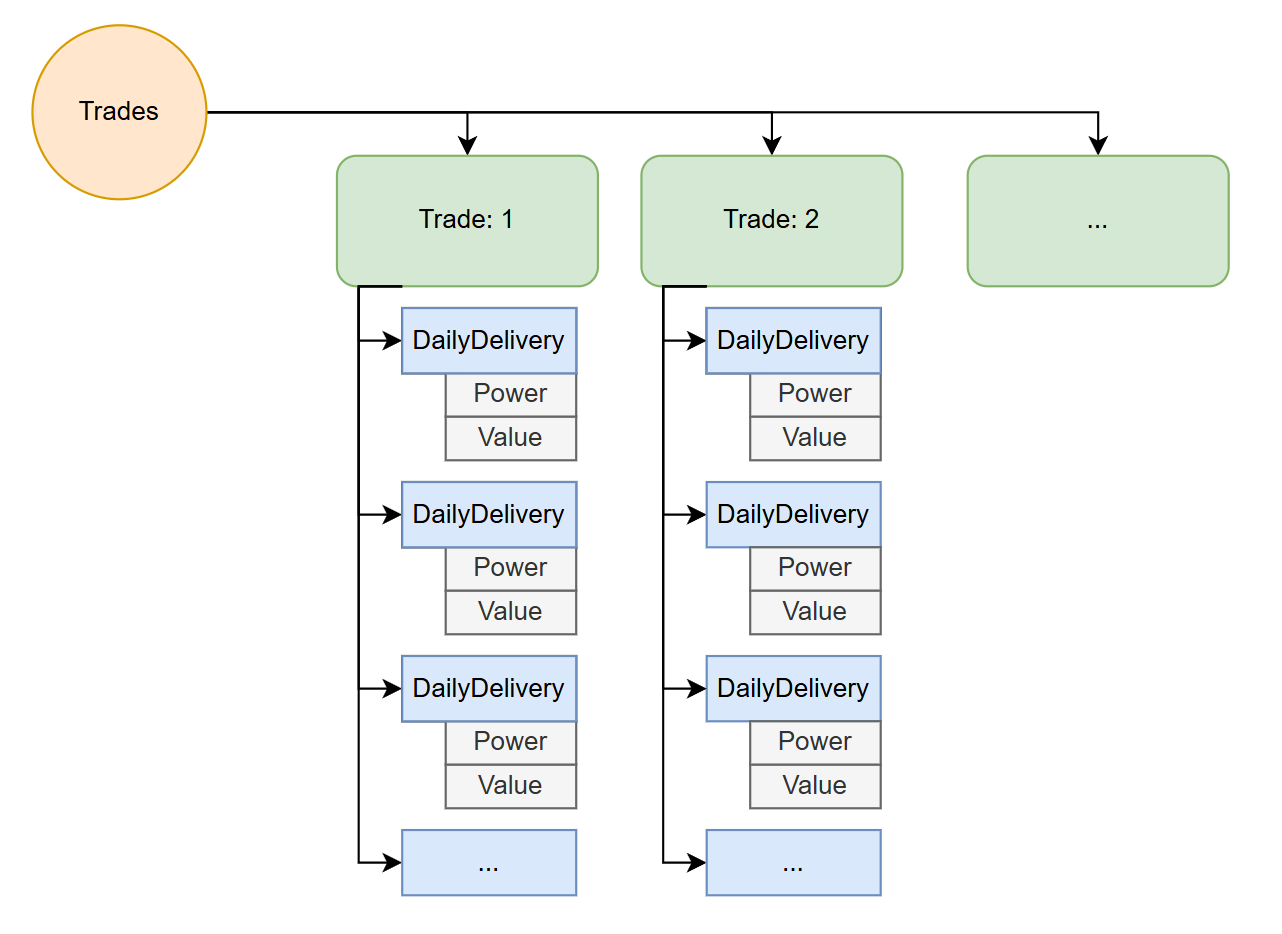

The initial implementation uses a std::vector<Trade> trades; with each trade maintaining a std::vector<DailyDelivery> dailyDeliveries; that contains the two vectors of power and value std::array<int, 100> power; std::array<int, 100> value;.

While vector does a great job at trying to get the memory allocated to it to be continuous in cpp, when you nest vectors in vectors and you allocate the sub-vectors, you are creating fragmented memory. This means the CPU's memory controller has to jump around a lot to get the next bloc and there's a high probability that adjacent will not be in the cache for the other cores of the CPU to be able to use.

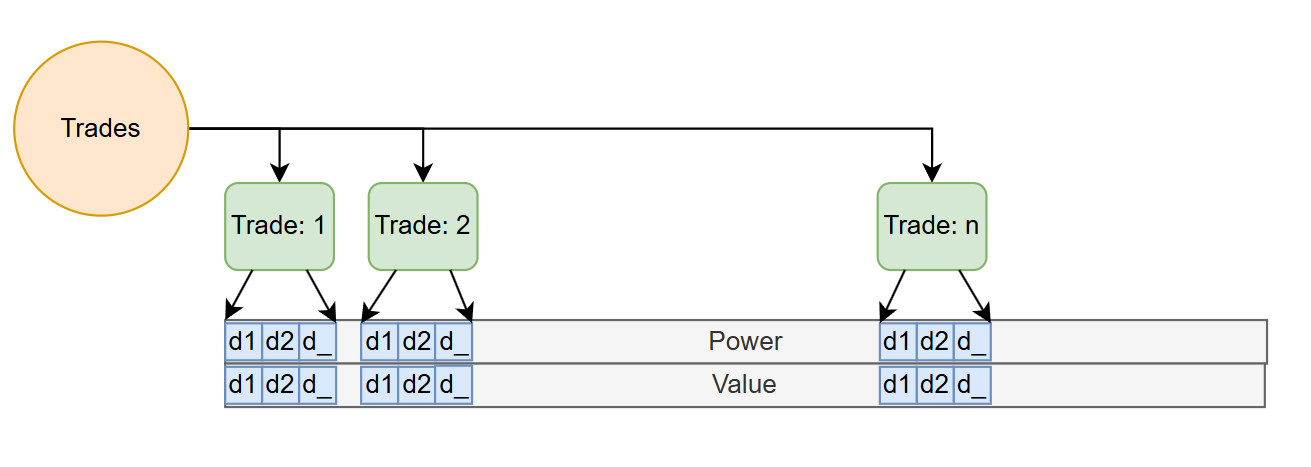

The best architecture for locality will be always dependent on the access patters to the data. In our case here, we are going to optimize for maximum speed when doing complete aggregations.

This is done by creating an specific area for the Power and Value data of each delivery day is allocated to. Trades point to the beginning and end of this data. If you need to move inside this area, because you know exactly the start delivery date of the trade and the size of the delivery day vector (100 ints), you can immediately index into the large array.

Now, if you are dealing with a small amount of trades (~50'000 with an average of 120 days of delivery ~~ 4.9 GB of RAM for 600 million quarter hours), you can get away with a single coherent bloc of RAM for your delivery vector. But see later for a more practical production discussion:

// Each daily delivery contributes 100 ints for power and 100 ints for value.

std::vector<int> flatPower(totalDailyDeliveries * 100);

std::vector<int> flatValue(totalDailyDeliveries * 100);

Now with this information, we can directly index into the area based on the trades data:

#ifdef _OPENMP

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+: all_totalPower, all_totalValue, \

traderX_totalPower, traderX_totalValue, \

traderX_area1_totalPower, traderX_area1_totalValue, \

traderX_area2_totalPower, traderX_area2_totalValue)

#endif

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < flatTrades.size(); ++i)

{

const auto& ft = flatTrades[i];

// Each trade's deliveries are stored in a contiguous block.

size_t startIndex = ft.deliveriesOffset * 100;

size_t numInts = ft.numDeliveries * 100;

long long sumPower = 0;

long long sumValue = 0;

for (size_t j = 0; j < numInts; ++j)

{

sumPower += flatPower[startIndex + j];

sumValue += flatValue[startIndex + j];

}

// (a) All trades

all_totalPower += sumPower;

all_totalValue += sumValue;

When running with this configuration, my time to aggregation on the laptop improves from 241ms to 178ms a 37% improvement in speed - which get us to 55 GB/s on a commodity laptop (using OpenMP of course).

Limits

But as you scale to larger and larger amounts of trades and delivery days, you will really find that the vector

At that point, we'll start running our own custom allocation, keeping our own block memory via a custom allocator. By creating blocks of 64 to 256MB that we allocate as needed and indexing our trade deliveries into it, we can then scale to more of the the entire memory of your machine.

Two good references on that are Custom Allocators in C++: High Performance Memory Management and CppCon 2017: Bob Steagall “How to Write a Custom Allocator”.

Next steps?

Going from a simple data structure to a memory adapted structure allowed us to go from 40GB/s (42% of laptop bandwidth) to 55GB/s (57% of laptop's 96 GB/s bandwidth).

If you still need more performance, you must further adapt your data structures and locality to the access patterns. Then start looking in depth at where the stalls are in the execution trace. There's other approaches such as looking at AVX instructions in more detail to find some perf, loop unrolling, and so on. Get a real cpp expert to consult on it.

Or just get a machine with more bandwidth! An example of that is the M2, M4 Max and Ultra family of chips from Apple, with memory bandwidth of over 800GB/s - over 8x what my laptop has. Or just run on a server, as noted in the first article, Azure has now a machine with 6'900 GB/s of bandwidth.